Tapestry. If you’re like me, the term conjures up mental images of slightly faded Renaissance scenes on giant fabric wall hangings in museums and old mansions.

Visit the new tapestry exhibition on the sixth floor of the Denver Art Museum, however, and you may find, as I have, that those mental images start to fray. Creative Crossroads: The Art of Tapestry includes two tapestries that fit that stereotype. Nonetheless, the exhibition has numerous other pieces that are quintessentially contemporary art.

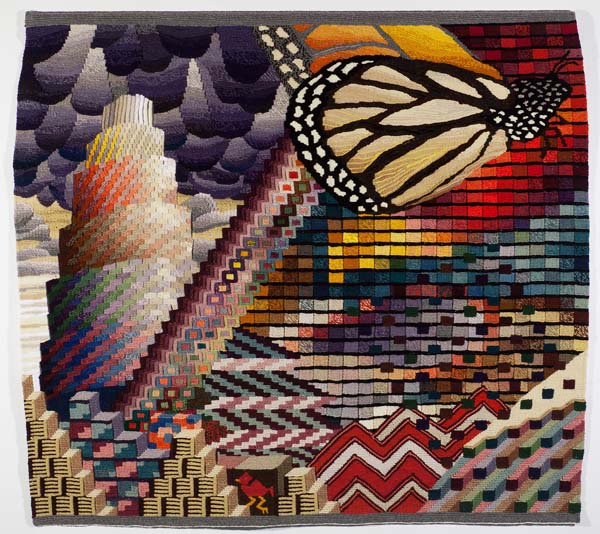

How contemporary can a tapestry be? This 4′ x 4′ work by fiber artist David Johnson suggests the answer. “Extreme Fibers,” formerly titled “Transformation,” will hang in the Muskegon Museum of Art this summer as part of its “Icons in Fiber and Textiles” exhibition. (Photo provided by D. Johnson)

In the Thread Studio next door to the exhibition hang small wooden looms with unfinished tapestries, silently inviting visitors to try their own hands at tapestry weaving. Twice a month, David Johnson, current president of Handweavers Guild of Boulder, sits nearby, weaving on a loom supported by his lap and the table in front of him. David himself set up the other looms for visitors to try.

David has been sharing his passion for fiber art and weaving at colleges and in workshops for decades. Here are some of the techniques and concepts he shared with me recently.

Getting the Big Picture

A vertical loom allows tapestry weaver David Johnson to see the picture he is creating as it will look when it hangs on a wall. (Photo provided by D. Johnson)

Weaving tapestry is like painting a picture with yarn instead of paint, David told me. To see clearly how the picture is developing, he and many other tapestry weavers use looms that stand perpendicular to the floor, like the one pictured here.

The white warp fibers are cotton seine twine, the same kind of fiber that fishermen in Europe have used for making nets. The warp completely disappears as David presses down each row of colorful, hand-dyed wool yarn (the weft) against the row below it.

To add texture to his work, David often mixes two types of weaving. The familiar weaving technique that takes the weft over one warp fiber and under the next (known to weavers as tabby) gives a very flat, even appearance to his tapestry. Placed next to tabby, soumac knots, which loop the wool yarn around the white seine twine, add dimension.

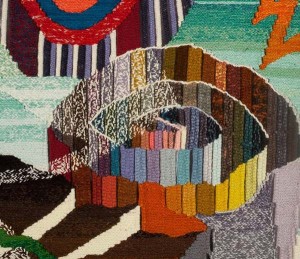

You can see the effect of soumac knots next to tabby in this close-up of another of David’s tapestries. The borders of the yellow and green stripes look as if he had knit the yarn, but the effect is actually created by weaving two rows of soumac knots side by side.

Multiple rows of soumac knots create another effect on the left edge and in the orange area in the lower right corner. The result is a thicker weave than tabby that literally brings those areas forward on the tapestry surface.

Instead of interlocking the yarn as he moves from one color to another, David makes the transition with slits. You could put a finger through the tapestry where the green stripe ends and gray begins. This style of weaving not only makes clean lines between colors but also allows the weaver to build up one area of color before moving to the next.

This unfinished tapestry by David Johnson includes an example of eccentric weaving in which the weft does not cross the warp in perpendicular lines.

Still a work in progress, this is what the tapestry looks like when you back up from it. The weaver’s term for the style of weaving in which the weft doesn’t cross perpendicular to the warp is eccentric. A handheld tool called a beater — essentially “a glorified kitchen fork,” David told me — allows him to press the lines of the weft against each other, even when the weaving is eccentric.

At the top left, leaves are pointing up into the empty warp. Tapestry weaving isn’t necessarily about working your way up the loom line by line from edge to edge, David explained. Often it’s about weaving small areas next to each other.

If you look very carefully, you may spot strands of yarn dangling from the leaves at the top and from the unfinished iris at the edge. As David continues to weave, he will pull those loose ends up so that they disappear under the yarn that fills in the tapestry above them. A picture of the back of the tapestry would look like the perfect mirror image of the front, with no signs of clipped yarn or random knots.

This simple outline, known in weaving as a “cartoon,” can be transferred to the warp on the loom to guide the tapestry weaver. David Johnson used this cartoon in his recent work.

What will the tapestry look like when it’s finished? Even David doesn’t know for sure. He enjoys building the design spontaneously, letting the completed components suggest the next.

If he decides to add more flowers, he will transfer a simple drawing to the warp to guide him. Tapestry weavers call such a drawing a “cartoon.”

After positioning the cartoon behind the warp, David uses a black marker to trace the design on the white twine. With just six warp fibers per inch on his loom, the traced guidelines look cryptic indeed.

David invests twelve to fourteen hours in every square foot of tapestry that he completes.

A Look at the Weaver

A passionate weaver with a wife and children, David doesn’t follow the norm in our culture. He is the first male president of Handweavers Guild of Boulder since the guild formed 51 years ago. Yet, it was a male instructor at Colorado State University, where he obtained a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, who introduced him to weaving. David had been drawn to the tactile experience of working with yarn since he made a hooked rug for art class in eighth grade. Working under Warren Seelig at CSU, David found his passion fanned by the combination of strength and suppleness that weaving brings out in fiber.

David Johnson and Geary Jones wove this detail extemporaneously into their collaborative work “Heaven and Earth.” (Photo provided by D. Johnson)

David smiles when he speaks of men and weaving. In Mexico and other parts of the world, men have been the weavers, he told me. Women have cleaned, carded, spun and dyed the yarn for the men to weave.

In the 1980s, David and fellow weaver Geary Jones collaborated on a series of contemporary tapestries. They wove in tandem, building on the area that the other had woven. Pictured here is a small section of detail from their work “Heaven and Earth.”

There’s a wonderful description of their vision and of David’s growth as an artist at the Arpana Annesha Studios website. David and Geary’s collaborative work will hang in a two-man exhibition this summer in the Lowell Art Center, about 30 miles from Muskegon.

You can see more of David’s tapestries in his photo album on Facebook.

A new post appears on Handmade on the Front Range every other Wednesday. Next post: July 1.

I have just finished Tracy Chevalier’s book “The Lady and the Unicorn,” which talks in great detail about the weaving of tapestries. I learned so much about the techniques and terminology, and today’s blog reinforces what I learned. The novel takes place in the 15th century, and the tapestries themselves are “woven” into the story line.

Sounds like a book worth reading. Thanks for sharing, Kathy.

I will look for the book, sounds great. Thanks.